Big data will change your life.

If it hasn't already.

September 2, 2016

The ability to harness and probe for understanding in massive amounts of data is heralding revolutionary approaches to the way we do business, provide healthcare and interact with each other.

So here you are. Reading this. From the moment you woke you've been leaving a trail of data 'crumbs', like a Hansel and Gretel of the digital world, which have the potential to reveal detailed insights into who you are and how you live.

It's a digital fingerprint that can reveal your behaviours and even predict your intentions.

Not convinced? Retrace your steps. You might have clicked a link to this story that appeared in your daily dose of information from Twitter, Facebook or in an email. And before that, you probably hit the snooze on an alarm built into a smartphone.

Perhaps you started your day by strapping on a smartwatch or heart rate monitor and hit the pavement for a jog.

As you worked up beads of sweat, an app or your watch recorded your route, time, speed, elevation and distance. On your way to work you may have used a transport smart card to tap on and pay your fare.

Next, you log into a server and check emails, browse websites and, eventually, end up here. Before you've had your first coffee you've left a trail of data, comprising bits of information faithfully recorded and logged on a network server somewhere.

And you are just one of millions upon millions of people worldwide contributing to an increasingly pile that we now commonly called 'big data'. Sound creepy? It could well be, and we'll get to that. But viewed another way, what if that data could be collated, with your permission, and used in a valuable way, such as improving your health and wellbeing?

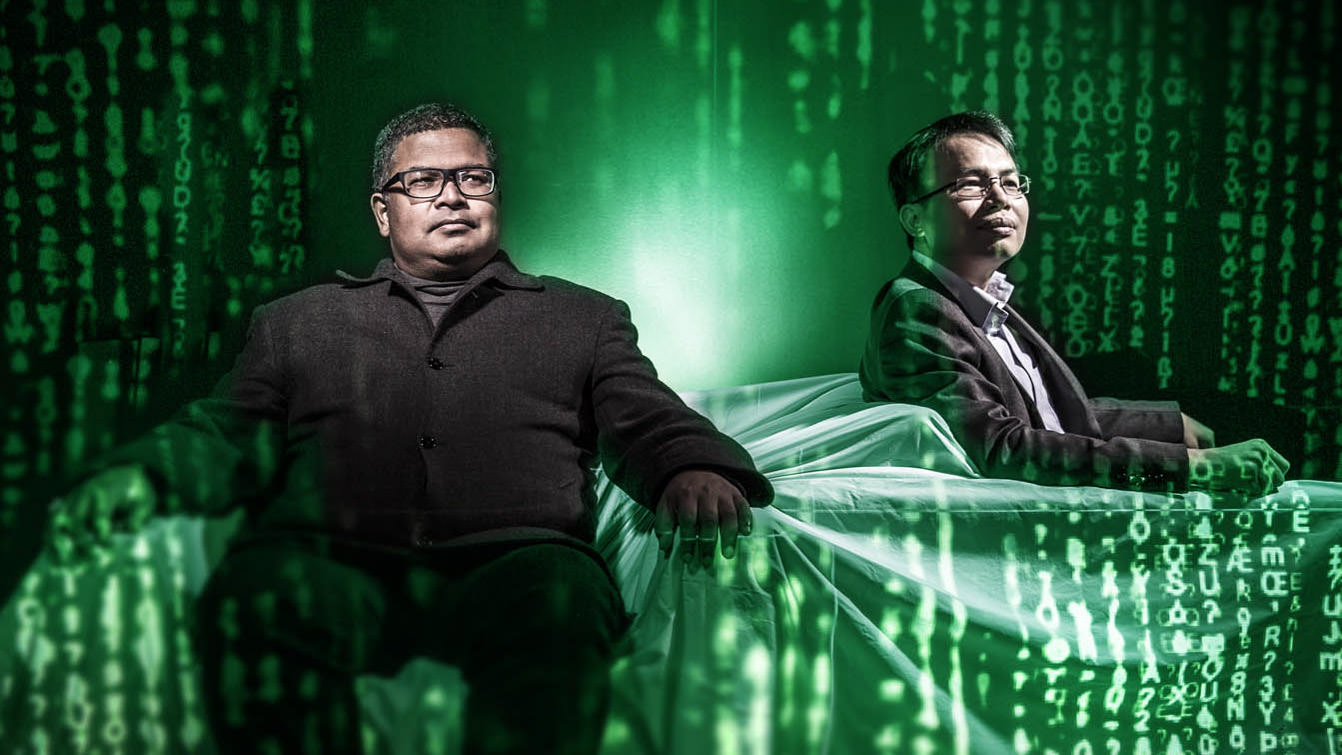

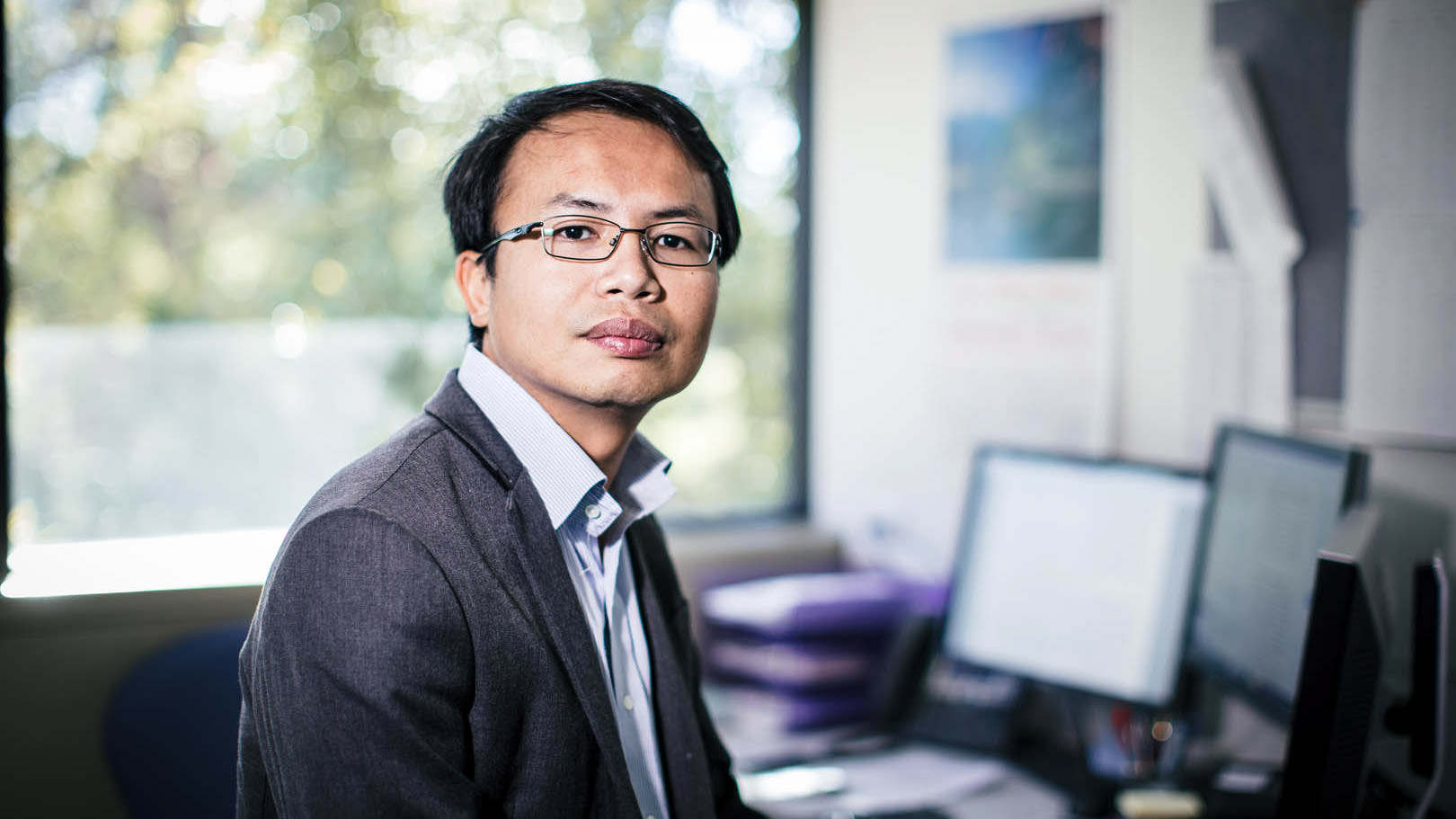

We are surrounded by data: numbers, words, locations, heartbeats, steps, web clicks. The trail of data we create as part of the rhythm of the human body and daily life largely goes unnoticed. Unless you are a data scientist like Professor Aditya Ghose from UOW's .

Professor Ghose and his colleagues are at the data mining coalface, developing increasingly sophisticated ways to extract insights to drive efficiency, productivity and potentially new ways of providing medical care. The world is catching on: from the steady flow of Harvard Business Review papers to the flood of marketing and technology blogs, everyone wants to know what to do with this data thing.

While the surge in the quantity of data is a phenomena in its own right, the more pertinent change, Professor Ghose says, is what we can learn from the reams of data: it has all the answers, the trick is asking the right question.

"We were working on extracting data to use in predictive models well before the 'big data' buzzword became popular, but when it did, it aligned very well with what we were doing," he says. "There were two catalysts for the emergence of significant interest in 'big' data.

"First, a new class of algorithms, the complex maths needed to interpret the data, for the very large volume of analytics. Second, and to a slightly lesser degree, is the technology in the form of significantly cheaper data storage and more powerful processing tools."

While the end goals of mining big data for uses in healthcare or marketing are worlds apart, stripped down to their underpinning data (under-data?), they are very much alike. And the emerging story could well be life-changing.

Social media semantics: is risquГ© an indicator of risky?

It was a website crash so colossal it had it's own hashtag: .

To the amazement of security experts across Australia, on night of 9 August the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) online Census crashed under the weight of hundreds of thousands of people attempting to complete the online survey.

It is the first time the ABS has attempted to carry out national survey online. UOW information security experts agreed that the situation was entirely preventable and planning for the event was inadequate.

Software failures of a grand scale are not isolated events. US President Barack Obama's Healthcare.gov crashed the day it launched (October 1, 2013). "Nobody's madder than me about the fact that the website isn't working as well as it should, which means it's gonna get fixed," President Obama said at the time.

With huge sums of money and smooth functioning of business and service provision at stake, no one in business, government or a public institution wants a major software project to run off the rails. Yet, the business of software development is rife with schedule overruns.

Unlike bricks and mortar construction, where risks with foul weather, materials delays and labour issues can be predicted with a degree of certainty, very little predicative ability exists to put a finger to the wind for major software projects.

With fellow researcher Dr Hoa Dam, from the Faculty of Engineering and Information Sciences, Professor Ghose led a project that looked at using words as a data source. They investigated social interactions of developers to see if their online chatter could reveal risks.

The theory was tested on five major open-source software projects, collecting data from each project's issue-tracking software. They recorded more than 40,000 logged issues and grouped them into 16 major risk factors that ranged from discussion time - how long the developers spent finding a solution to an issue - through to complaints about developer workload.

"The 'chat' around issues was a sort of social network and the language used was very useful in identifying risks and building a model to predict their impact on a project's release date," Professor Ghose says.

"From there we developed accurate models to predict whether an issue would cause a delay, and if so, what impact it would have, as well as the likelihood of the risk occurring. The next task is providing various actionable recommendations such as which risks should be dealt with first."

While the predictive model for project risks and delays, published in a recent paper, was highly useful, Professor Ghose says it opens the door to a host of other social media data mining applications.

"Mining social media is an example of how indirect data trails can reveal reliable insights. Applying the same logic as the software project, a personal social media network can be mined to identify that person's creditworthiness. For many young people, lacking a credit history, this can be critical in securing loans, or even the likely high school scores."

That sound you hear is your in-built privacy alarm. No doubt there are serious ethical and privacy implications to that idea, but as Professor Ghose points out, it testifies to the power of the logic to show what can be done by turning idle chatter into data.

Data-driven health and happiness

The idea that meticulously recorded data about patient treatments and outcomes improves medical practices is not new. In the mid-1800s, American surgeon , who pioneered the radical mastectomy, was known for his scrupulous recording of data on treatments and outcomes.

Though much data are currently recorded by medical services, Professor Ghose says it's often badly recorded and isolated, in part for privacy reasons. The emerging field of clinical informatics seeks to help medicine with answers to its most pressing questions by applying data-mining techniques adapted from business to bring disparate data together and find meaningful insights.

"Given that we still don't understand the biological pathways involved in cancer very well, our best bet is to view correlations in data as a proxy for causation."

Professor Ghose's team collaborates with an international network of radiation oncologists and radiation physicists to extract data sets and mine for treatment processes that lead to good outcomes. Ultimately, the intent is to gain insights into correlations between patient features, treatments and patient outcomes.

"One of the challenges in doing this is mining data located across a network of hospitals and medical centres. Our laws prevent the data from moving outside the hospitals where the data originated, but reliable insights can only be mined from bringing all of this data into a single data store."

Professor Ghose's team has developed techniques for mining clinical process insights by viewing this network of data as if it were located in a single data store. This ensures that the data does not move, thus preserving patient privacy.

Mining treatment process data can also improve understanding of how to execute these processes in a more efficient fashion. Efficient processes lead to better use of scarce medical resources, but can also have important implications for patient outcomes.

For instance, for fast-growing cancers, it is important to ensure that treatment planning processes execute as quickly as possible, so that treatment can start as soon as possible.This allows them to build a model a doctor can use to input the treatment plan and patient characteristics and calculate the chines of survival.

Ultimately, this saves critical time in the treatment planning phase.

Business process management

The buzz around big data in business focuses mostly on customer insights for sales and marketing. Professor Ghose is more interested in increasing profit margins by looking at what happens in the operations rooms rather than on the sales floors.

"The business world faces two competing challenges: to do more with less, while at the same time meeting increasing customer service expectations." Professor Ghose says the result has been the emerging field of 'service science' as an attempt at understanding how enterprises work in an integrated, holistic fashion.

The problem has been that efforts to analyse team performance has largely focussed on the human element, and attempts to equate complex behaviours into machine-like performance data is fraught with danger and could provide inaccurate results.

Yet, employees in businesses press keys and swipe cards, leaving a trail of data in the form of process logs and message logs, for example, which can be mined and analysed for performance insights. That theory has been tested on IT support, services that are often outsourced to third parties who deliver remotely.

"These types of businesses simply don't have an accurate idea of how big their teams should be. To avoid penalties in meeting contract obligations, these services over-staff, which leads to inefficiency and higher operating costs. A number large service organisations are overstaffed, sometimes by up to 40 per cent of their workforce.

"This creates massive inefficiency. We have shown that a combination of data analytics, agent-based simulation and distributed optimization can be a game-changer in this space"

Once the team has built a picture of the process, it could model new workflows that optimise productivity and efficiency that could eventually enable managers to make informed decisions about task allocations to team member, and thus the size of their teams. An extension of the research is introducing 'context-aware' modelling to that takes into account factors that impact on performance.

"Each log has a time stamp and we can check that against media reports and weather reports for the context. We know that during bad economic times, there are major delays in executing financial processes because people more likely to be unhappy.

"This allows us to introduce richer planning models that allocate staff and resources according to the context of the day. There are serious gains to be made by using an automated work assignment system that dispatches tasks based on those two findings."

Of course, big data is not a cure-all and when it comes to business improvement, the computer science adage remains apt: 'garbage in, garbage out'.

A word of caution

The takeaway lesson is the massive potential for advances and improvements in health services and treatments as well as new ways for governments and departments to truly consult their communities - all positive advances.

The flipside is that for each advance, the big data scenario serves up social and ethical implications, the consequences of which are the focus of study for Professor Katina Michael from UOW's School of Computing and Information Technology.

"What happens when we start using these data collection and analytical practices at birth? It means a child born into the world will be screened for defects, which could mean a better care management plan, but it opens the door to the prospect of social sorting and possible victimisation, being denied access to insurance and on it goes.

"In a business application, tracking employees' every move and continuously measuring their performance against industry benchmarks introduces a level of oversight that can quash the human spirit. Such monitoring might be in the best interest of a corporation but is not always in the best interest of the people who make up that corporation."

In her 2009 book, , Professor Michael writes that "technology-push" rather than "market-pull" is driving the uptake of new technology, such as implantable medical devices, location-aware services and business services that use automatic identification. One-step logins spring to mind.

Professor Michael believes this cart-before-the-horse scenario is blissful ignorance and it's our duty as citizens to decide the path we want to tread before we lace up our shoes. The oft-quoted Latin phrase is certainly not out of place: Caveat emptor (Let the buyer beware).

"We can live with many of these uncertainties for now with the hope that the benefits of big data will outweigh the harms, but we shouldn't blind ourselves to the possible irreversibility of changes - whether good or bad - to society."

And, less sinister but not less worthy of debate, is data making life boring simply by turning natural and at times pleasurable human activity into a data set of likes and shares?

"Big data are most emphatically not a cure-all," Professor Ghose says. "The complex web of knowledge within which the data is situated is important. Human curiosity, intuition and intellectual ambition remain as important as ever."