Subscribe to The Stand

Want more UOW feature stories delivered to your inbox?

How a rural medical training program is reducing healthcare inequality in regional Australia.

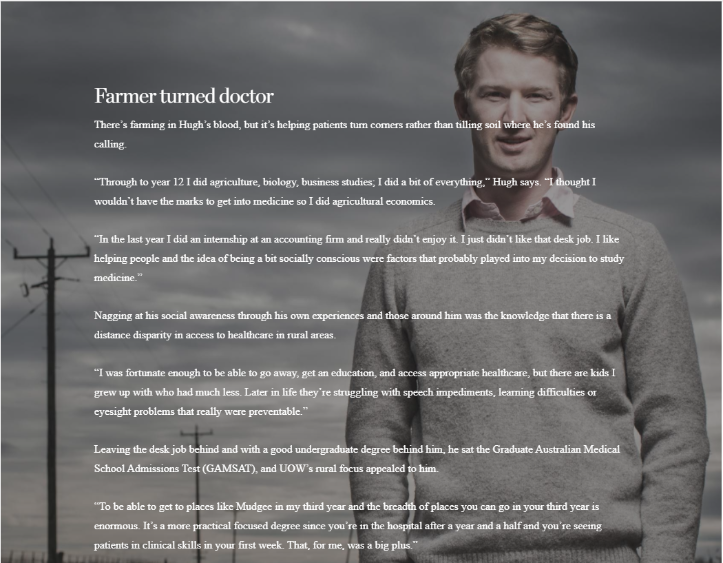

He's baked a cake for theatre staff as a small gesture of thanks to those he was worked with. The joke doing the rounds is that as a baker, Hugh will make a great doctor. During mid-June, the students sat series of rigorous practical and theoretical exams as part of their progression from students to junior doctors. Hugh's class is one of many that highlight UOW's commitment to securing a stable medical workforce in regional, rural and remote areas.

Earlier this year, debate arose about the number of doctors being trained in Australia. The argument went that , which, according to Australian Population Research Institute, increased by almost one quarter (24.1 per cent) in the decade to 2015, and the oversupply is driving up the cost of providing taxpayer-funded healthcare.

The more nuanced argument is that there are enough doctors being trained, but the distribution - where they end up working - is out of balance. That's where students like Hugh come in. Since the establishment of graduate medicine in 2007, it has maintained a core focus on training doctors with the capacity and desire to work in regional, rural and remote communities.In fact, UOW GM is the only medical school in Australia to give all students the opportunity to undertake a 12-month clinical placement in a regional or rural setting and it attracts a large proportion of students from outside the major cities. The people behind the program are confident the strategy is working: to date, 464 students have graduated having been specifically trained to deliver healthcare in Australia's rural, regional and remote communities.

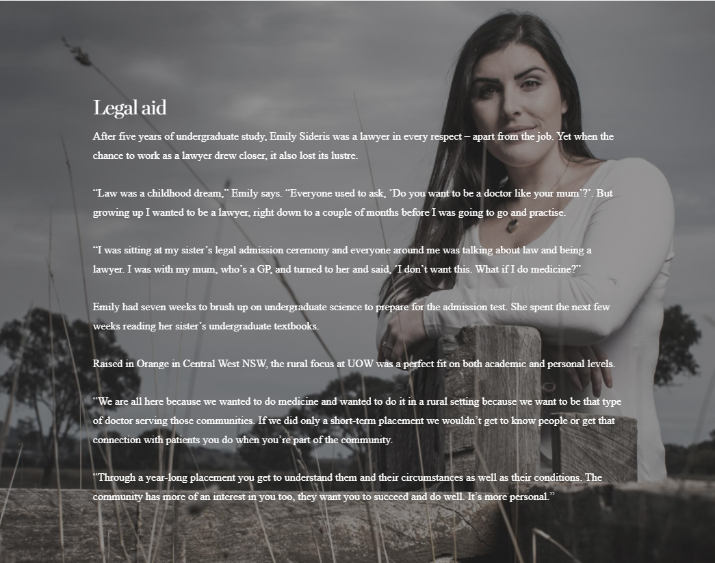

That process is helping to solve one half of the healthcare equality equation. What remains to be addressed is the bottleneck in specialty training that will enable these graduates to access the programs needed to keep them connected with rural communities. "We don't need any more medical schools," Student Emily Sideris says. She has also spent the past year in Mudgee with the program. "The bottleneck in the system is in speciality training."

It's the system of teaching and developing critical medical skills that is being hauled into the policy-making emergency department. More recently, a joint proposal for a '' was drafted by the Rural Doctors Association of Australia (RDAA) and Australian Medical Association (AMA). It takes a two-pronged approach: first by encouraging more doctors and other medical professionals to work in rural areas with the incentive of a 'rural isolation payment'.

The second prong involves a rural generalist training program to equip doctors with advanced skills, such as "obstetrics, surgery, anaesthesia, acute mental health, or emergency medicine" to not only fill gaps but add valuable skills. According to Associate Professor David Garne, UOW GM Associate Dean: Community, Primary, Remote and Rural, the two strongest predictors of a student going on to work in a rural area are if they have a rural background and already have a connection.

The second is a significant positive training experience in a rural setting. "About two-thirds of our students have a rural origin, which is the highest in the state," he says. "We also give them a good positive rural training experience. During the four years that they're with us they all rural training in some form or another. But it's the postgraduate rural training in rural areas that is the problem now. It's the postgraduate training bottleneck they need to address."

The bottleneck is creating pressure on students like Emily and Hugh, who would like to work in a rural or regional area but face strong competition for the necessary specialty training.

"The number of students coming through, it's an absolute tidal wave that the training programs aren't prepared for," Hugh says. "Every university would probably like to have a medical school but they need to assess whether these schools do get people back to rural areas before they start opening more."

The UOW GM-proposed solution is to get the right sort of supervision and support for additional training positions in rural areas, rather than funnel students back to the cities for what limited places are on offer. "If we look for rural settings where there are opportunities for training and make sure the specialist supervision gets put in place, we can then expand training places," Professor Garne says.

"There are smaller places where there is the capacity and potential given the right support. The trainees might not be able to do all their training in a rural place, but why not do the bulk of it there and rotate into the cities for the training they can't get rather than the other way around. We need to flip it on its head, turn it over. The program is doing remarkably well, the onus is now on us to show that we are in fact achieving our mission of producing doctors to work long-term in rural settings."

Regional, rural and remote. It is something of a mantra at UOW GM to support their mission of producing doctors for the bush. From the moment the students arrive and throughout the curriculum they are challenged to think about how they would apply what they are learning if they were working in the bush. With roughly one-third of Australia's population, around 7 million people, living in rural, regional and remote areas, with some of the lowest population densities in the world, it's vital the students have the foundation to be able to cope and prosper professionally and personally.

Their main challenge will always be the tyranny of distance. To illustrate: students working with the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) out of Broken Hill will travel across the sparsely populated interior of western NSW, the south-western corner of Queensland and the north-eastern corner of South Australia - a total of about 640,000 square kilometres, which is about the size of England and Wales combined. Professor Garne, spent seven years in Broken Hill with the RFDS and knows from experience the challenges the students face.

"I think the reality dawns on day one that you're working in a very, very different setting and you just have to be prepared for anything. You certainly have to have a certain amount of resilience to cope with the different way you practise medicine. It was a steep learning curve, going from a suburban general practice to dealing with major, life-threatening emergencies in resource-poor settings. With the right sort of training and support it wasn't necessarily a problem. I probably do have one regret and it's that I didn't go to Broken Hill sooner than I did."

He says setting up students for success starts with the recruitment process. "We give a positive weighting to applicants with a rural background and a strong connection to rural areas. No matter where they come from they know what our program is before they enrol. They know our mission is rurally focused and that's what they sign up to." The long-term placement gives the students a much deeper immersion in the community, as well as providing continuity of patient care, academic supervision and curriculum.

"Students on short-term placements are basically just there as tourists."

- Associate Professor David Garne

"They enjoy it, they have a nice time, but they go back to where they came from and those memories soon fade. You get a taste, but that's all. We lay the foundation for students to work in any field of medicine and any setting they choose and we try to show them that working rurally is very rewarding and it can be pleasant and productive fulfilling lifestyle. There's payoff in longer placements for the clinical supervisors as well.

"It takes time and effort for local staff to get new students oriented and up to speed with what's expected in a rural practice. "If you have a new student coming through the door every four weeks gets tiring," Professor Garne says. "It gives them a sense that if the student enjoys their stay, there's a much greater chance they're going to come back once they've finished training and become part of the workforce. So the investment they make is more worth their while."

In practice, the 'three Rs' stretches the students to think and apply core medical skills. Emily says that being rural means they need to be conscious of the services that can be offered. "You have to think about transport times and availability, you can't just write a referral, just go get an x-ray, CT scan or MRI - you really need to rely on your skills," she says. "If you're in the emergency department with a patient and it's 8pm and the radiographer has gone home, you can't just order a scan.

"You need to rely on your skills to do a proper examination right then and there to see how serious their condition is, so you can determine whether you're calling the radiographer back, urgently moving them or if they can go home for the night. These are critical skills. Perhaps most tellingly, it's the experiences the students themselves have that will ultimately lead to a desire to work in a rural area or be drawn to the bright lights of the city.

After his year, Hugh says his experience in Mudgee has shaped his decision to one-day return to a rural area to work. "Getting to know the patients over the year, that in itself was an amazing experience," Hugh says. "Just seeing people progress through the highs and lows, like seeing an old fella come in with severe osteoarthritis and being incredibly restricted physically and mentally by it, after which you follow him through his surgery and recovery. It's very rewarding having that continuity of care.

"Or having a mother come in for preconception planning, falling pregnant and then delivering the baby; you just can't beat it."

Words: Grant Reynolds Photos: Paul Jones